Introduction to Pooling and Servicing Agreements

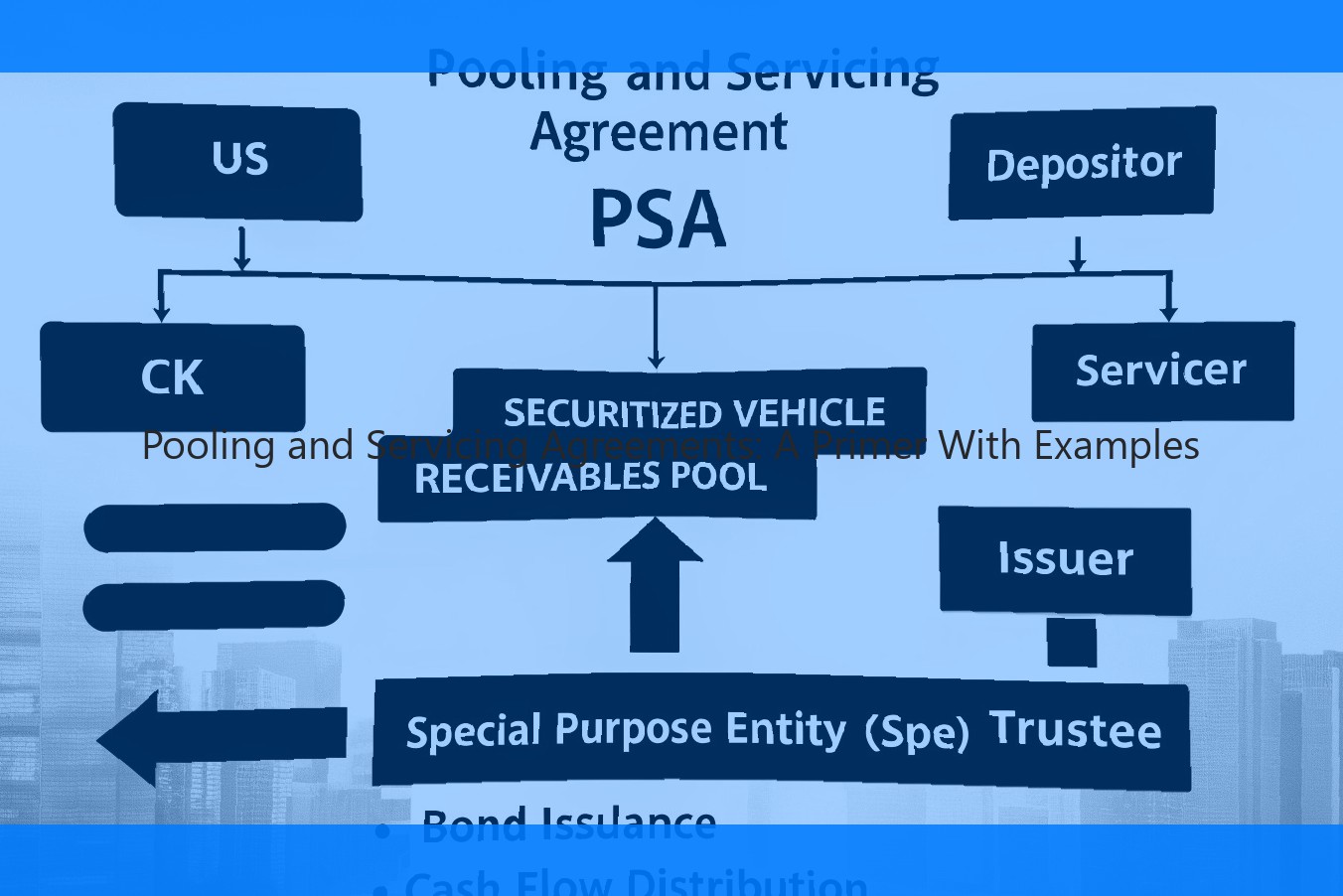

Pooling and Servicing Agreements (or "PSAs") are the keystone documents that govern securitized vehicle transactions. They establish the contractual framework for a securitization. As the name suggests, pooling and servicing agreements describe a multi-step process. For starters, a newly formed securitized vehicle must find a source of receivables to purchase. In some cases, the new entity will already have identified a particular pool. In others, the entity (typically represented by a bank) will identify pools through a series of transactions. After identifying a pool, the entity will enter into a sale agreement with an originator, allowing the entity to purchase the pool in its entirety. With the pool in hand, the newly formed entity almost always transfers the pool to a newly created special purpose entity (or "SPE"). This SPE will put together the securitization by selling bonds to investors following the legal process for securitization.

Pooling and servicing agreements are among the most generic of all asset-backed securities documentation. They almost always abide by the template put in place in the 1990s by the American Securitization Forum (the "ASF"), which the ASF modified in the 2005 version it calls the "ASF 2005-1" form. A PSA generally states that the parties thereto agree that the "Transferor" will transfer its interest in the pool to the "Depositor," which will then sell the pool to the "Issuing Entity" in exchange for senior and subordinate notes representing debt. The Entity will then issue asset backed notes in a multi-tranch form (tranches vary by risk and reward by degree of credit rating), and the Issuer will then deposit the notes with the "Indenture Trustee" for safekeeping until such time as needed to facilitate the transaction . The Depositor will act in the interests of the Issuer as the servicer and delegate specific duties to the "Master Servicer."

Pooling and servicing agreements clearly state the SPE’s obligation to follow certain flow of funds rules, governing the distribution of cash received from the pool to the various bondholders. Section 9.03 of the ASF form sets forth the distribution process as follows: The Issuer shall distribute to each Certificateholder, the Class Principal Distributions on each Distribution Date, and each Holder of a Class [•] Certificate shall share in such class distributions on an pro-rata basis or as otherwise provided in this Agreement, to the extent funds are available; provided, however, that on any Distribution Date other than the final Distribution Date, the Issuer may deduct the amounts, if any, to be deposited in the Reserve Account and the Class [•] Interest Distributions payable to each Class Certificateholder pursuant to this Agreement from such Class Principal Distributions otherwise distributable to such Class Certificateholder.

The PSA usually identifies the following parties: "Depositor" – the party that deposits the pool of underlying assets in an SPE, the Depositor is the entity that typically purchases the pool from the seller or the originating entity. "Servicer" – the entity responsible for administering the pool after the closing of the securitization transaction and ensuring that all loan payments are collected and that the lenders are paid. The servicer typically processes principal and interest payments collected on the pool, collects late fees, and receives and distributes all required certifications. "The "Issuer" or "Issuing Entity" – an entity created solely for the purpose of acting as the issuer of the bond certificates. An Issuer will typically be a statutory or business trust.

Components of Pooling and Servicing Agreements

The key components of a pooling and servicing agreement typically include: (i) the parties involved; (ii) the assets being held in the trust; (iii) the representations and warranties, covenants and indemnifications regarding the assets; (iv) the servicing and administration of the assets; (v) the rights of the parties with respect to the assets; (vi) the collections and distributions process; (vii) the investment of funds; (viii) the reporting requirements; (ix) the form of payment; (x) the rights of the parties in the event of an event of default; and (xi) the termination of the trust, amongst other details regarding the operation and management of the trust.

Parties could include the depositor, the servicer, the trustee, the fiscal agent, the bondholders and various other parties. The depositor is the party that sells the assets to the trust and holds the trust certificates, whereas the servicer is a person or entity that manages the assets, collecting, administering and remitting collections from the borrowings on the assets. The trustee typically oversees the selling of the securities to the public and the administration of the indenture.

The depositor and the servicer can be the same or different entities and the servicer can be a part of the securitization. The role of the trustee can be held by an institution such as a bank that is located in New York. The trustee executes the actual sale of the securities. The fiscal agent is the entity that distributes the payings of money to the investors. The indenture trustee is essentially the owner of the collateral, but holds it for the benefit of the investors.

Pooling and Servicing Agreement: Step by Step

Suppose an originator such as Michigan Valley Mortgage Corporation (the "Originator" or "OP") sells a pool of residential mortgage loans to a Depositor (such as Michigan Valley Mortgage Securities Corp.) The Depositor sells those mortgage loans to an issuer (Mortgage Backed Securities Trust) to be funded with the proceeds from the issuance of notes. The issuer has a master indenture with a party unrelated to the issuer (a master indenture trustee (the "Indenture Trustee")) that acts for the benefit of the noteholders and a subindenture with a custodian (National Registered Agents, Inc., the "Custodian") to hold the mortgage loans on behalf of the Indenture Trustee for the benefit of the noteholders. The Originator retains Owings & Wolff, Inc., an experienced servicer (the "Master Servicer") to service the mortgage loans. The Master Servicer and Depositor enter into a Master Servicing Agreement pursuant to which the Master Servicer takes delivery of the mortgage loans from the Custodian or Indenture Trustee and services and administers those mortgage loans pursuant to the Master Servicing Agreement on behalf of the Depositor, as outlined herein. In order to accomplish this, the origination and structure steps are as follows:

- The Originator could sell the mortgage loans to the Depositor under the Sale and Servicing Agreement structured such that the Originator would continue to service the mortgage loans on behalf of the Depositor.

- The Depositor transfers the mortgage loans to the issuer pursuant to a Mortgage Loan Sale and Purchase Agreement and the Depositor assigns certain of its rights against the Originator (as outlined in the Sale and Servicing Agreement) to the Issuer.

- The issuer transfers the mortgage loans to the Indenture Trustee pursuant to a Master Mortgagor Credit Agreement using a Sub-Servicing Agreement.

- The issuer issues notes paid with interest of specified amounts to separate classes of investors. The proceeds from the sale of those securities are used to pay the issuer for the purchase of the mortgage loans.

- Under the Sub-Indenture, the custodian (also an unrelated third party) acts as agent for the Depositor to take delivery of the mortgage loan documents from the Originator, hold those documents for the benefit of the Indenture Trustee, assume the responsibilities of a disbursement agent and other agents in connection with the new loan documents and deliver the mortgage loans to the Custodian. Agents owe fiduciary duties to their principal. This is another example of an agency relationship and there is an implied covenant that the party designated as the agent (here "Custodian") will act in good faith.

- As stated above, in the Sale and Servicing Agreement, the service and administration of the mortgage loans shall be performed by the Master Servicer. The Sale and Servicing Agreement would set forth how that will be accomplished, including contractually allocating risk between the Originator and the Depositor and the Master Servicer and its subservicers, if any, e.g., whether credit risk is retained by the Originator or passed to the Master Servicer or the Depositor. As between servicers, only the Master Servicer (here Michigan Valley Mortgage, Inc.) is (i) liable for loss upon misappropriation of funds collected by any of the Servicer’s subservicers (ii) required to compensate to the Depositor for monthly shortfalls. Thus, the risk allocation provisions shall be established in the sale and servicing agreement.

Pros and Cons of Pooling and Servicing Agreements

Investors and financial institutions may identify some advantages from the use of pooling and servicing agreements (PSAs). PSAs facilitate the securitization of mortgage loans and create secondary markets. Lower costs of funding and enhanced financial liquidity are typically beneficial to financial institutions. In addition, collections on mortgage loans are often more easily enforceable in the context of a PSA than when involving multiple parties. The sale of mortgage assets without recourse on the seller reduces the risk exposure for the seller. An important benefit for investors is that investors in mortgage-backed securities often receive a higher credit rating for such securities than the credit rating of the mortgage loans in the relevant trust. Credit rating agencies such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s have developed a sophisticated model of risk assessment, which allows the credit rating agencies to predict with a high degree of accuracy what mortgage loan backed securities will perform well, and which will not.

The PSA concept is not risk-free, and capital markets may be weakened if insufficient transparency exists in the structuring or enforcement of PSAs. Without the highest quality legal documentation, PSAs may come under judicial attack. The layering of interests and contractual relationships can create an unnecessarily complex structure that, in some circumstances, is inconsistent. Sophisticated investors or mortgage borrowers should not underestimate the consequences of an ill-defined PSA. Because each PSA is unique, great care must be taken in how the PSA is drafted, interpreted, and if necessary, amended. For example, in re Discipline of the Bar, 51 P.3d 1007 (Cal. 2002), the California Supreme Court issued an opinion addressing a dispute among investors in CMOs over an CMO sponsor’s inability to execute the necessary PSAs. A result of the problem, a special purpose vehicle was unable to provide the assets necessary to complete the PSA, thus defaulting on the contract. The court noted the differing definitions of what constituted a PSA, with much of the language contained in the PSA similar, but certainly not identical. The court concluded that there was no undue burden on the PSA that would cause an involuntary bankruptcy, and that there were reasonable efforts by the debtor to negotiate a solution.

Laws, Rules, and Regulations

Pooling and Servicing Agreements (PSAs) govern the operation of asset-backed securities (ABS) trusts. Particularly in the wake of the recent financial crisis, regulators remain active in their oversight of all component aspects of ABS, including pooling and servicing agreements.

In addition to the detailed set of contractual requirements imposed by PSAs themselves, both general and specialized regulatory compliance requirements are placed on parties involved with pools of ABS. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), each state’s securities agency, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) all play roles in regulating ABS and their servicing.

For example, in many cases, REMICs (real estate mortgage investment conduits) are the investment vehicle used to hold pools of mortgages. As such, the activities of these vehicles are federally regulated in large part by the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The IRC imposes certain compliance obligations on REMICs, including requirements to have remedied any "defective contracts" before allocation of income or loss from those contracts. For a contract to be a "defective contract," the IRS requires that the contract be a modification of an existing contract, and that the modification results in an addition or deletion of a substantial amount of cash flows derived from the contract; or that the contract must provide for either a substantially increased stated interest rate or a provision that the holder may receive amounts in addition to stated interest payments. If such a contract is entered into, the IRS requires correction by the earlier of the close of the calendar year in which it was entered into, or the due date of the trust’s federal income tax return for that calendar year (including any extensions of time). Additionally, the IRS requires that tax-exempt parties notify the trust manager of any "prohibited person" status if the value of the property attributable to all tax-exempt parties exceeds 10% of the value of all the property held by the trust .

However, regardless of and in addition to these IRS requirements, the pooling and servicing agreements themselves generally impose further regulatory obligations on the trusts, servicers, and sellers of the mortgage properties held in the trust. One example of such a requirement is in the Certificates Series PSAs, which require that certain regulated entities (such as federal savings associations and federally insured national banks) not be "sanctionable persons" at the time that the pooling and servicing agreement was executed. "Sanctionable persons" are those restricted from doing business by either the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). This prohibition is general in application, and does not appear to allow exemptions for lower-level employees. Other examples of regulatory compliance obligations imposed by PSAs come from the Dodd-Frank Act. Such obligations include requirements that servicers retain, in some cases, owners of residential mortgage backed securities (RMBS) in connection with the performance of certain CMBS (commercial mortgage-backed securities). Another example comes from section 932(b) of the Dodd-Frank Act, which requires the establishment of a risk-retention requirement for sponsors of ABS. In an effort to ensure proper alignment of interests, this section also requires that top management must not reduce the interest of a sponsor in the pool of ABS, prior to the repayment of the asset-backed security.

Regulatory compliance obligations can come from other sources also. For instance, in some instances, non-compliance with pooling and servicing agreement regulations can in turn trigger compliance with regulations of federal, state, or local authorities, like those of HUD or the CFPB. Compliance with pooling and servicing agreement regulations can also trigger compliance with requirements adopted by state certification boards as well, such as the Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSE) requirements, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Non-compliance can in turn trigger imposition of large monetary penalties, such as the $3.2 billion penalty imposed on Bank of America in 2014 for failing to adhere to its pooling and servicing agreement requirements to "buy back" defective loans. The prompt identification and rectification of issues and compliance failures are thus crucial to prevention of long-term liability.

Pooling and Servicing Agreement Provisions

A fundamental aspect of the pooling and servicing agreement is the servicing fee, which compensates the servicer for its services in administering the mortgage pool. The servicing fee clause will set forth the amount of the fee, the date on which the fee will be paid, and the manner in which the fee is to be calculated. One common formula provides that the servicing fee will be 1/12 of either (1) a specified percentage of the remaining unpaid principal balance as of the preceding determination date, or an alternate percentage of the sum of the aggregate unpaid principal balance of the mortgage loans over a specified period, or (2) the sum of actual costs and expenses incurred by the servicer in performing its servicing functions, or a percentage of the remaining unpaid principal balance of the mortgage loans, provided that the servicing fee, once calculated, cannot increase above the specified percentage.

Another often-encountered clause is the default and remedies clause. The clauses define events of default, the extent of the servicer’s authority to take certain actions in the event of a default, and the remedies available to the depositor (and, ultimately, the certificateholders) in the event the servicer defaults.

Indemnification clauses specify the standard of conduct required of each party in order to be indemnified against any resulting costs, and exclude from indemnification any losses resulting from fraud, willful misconduct, or gross negligence. Indemnification clauses often survive the termination of a pooling and servicing agreement.

The Future of Pooling and Servicing Agreements

Emerging market trends and technological advances will continue to shape the evolution of pooling and servicing agreements. One central question is whether accounting changes will become effective in public/private sponsored transactions. The Accounting Changes and the Transition Period for Issuers and Acquirers of Certain Mortgage-Backed Securities was published by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in June 2015. The FASB Accounting Standards Update, which is included in the document, states that one of the key features of the amendment is to provide guidance on the accounting of the derecognition of transferred assets and the recognition of financial assets of securitization transactions. Securitization entities will now be required to determine if the assets are being delivered by the transferor or if control is being surrendered. The financial assets will be considered to have been surrendered if the transferor has relinquished control. This change in accounting practices for issuers and acquirers of certain mortgage-backed securities provides an option to avoid retroactive application of this approach until annual periods beginning after December 15, 2016. Public entities have until December 15, 2015 to implement these accounting changes. Private entities as defined by GAAP are now entitled to follow a private company alternative if their securitization structure meets specific criteria: (1) they have debt securities, that are claimed to be held by an external party, that are not traded on a public information exchange, (2) the debt securities do not have multiple issuances and (3) the financial information or financial statements are not publicly available. Both public and private entities may utilize this private company alternative until annual periods beginning after December 15, 2016. The implementation of the new accounting changes will continue to drive innovation among market participants in regard to pooling and servicing agreements. Standardization across the mortgage-backed securities industry will foster transparency and reduce counterparty risk both domestically and globally.

Conclusion: The Role of Pooling and Servicing Agreements

In conclusion, pooling and servicing agreements (PSAs) are contracts that have been pivotal in transforming the U.S. mortgage market. They are now used for various types of asset-backed securities (ABS) that allow banks to pool together hundreds or thousands of loans and issue them to investors as high-quality securities.

PSAs established standards that defined the roles and expectations of participants in a securitization, bringing uniformity to a diverse and complex market. In addition to helping facilitate securitization in a relatively uncomplicated fashion, PSAs increased the transparency of securities offerings. This was especially important for introducing the non-agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) asset class to the capital markets. Investors , rating agencies and the market had a standard form on which to rely.

In an increasingly complex financing environment, PSAs play a crucial role in enabling the creation of ABS that allow companies and individuals to acquire vehicles or homes. Through the securitization process, financial institutions are able to consolidate and sell loans as securities, recovering their investment and providing debt capital to expand. For those investors that buy them, ABS are often relatively low-risk, providing stable cash flows.

The past several decades have seen an unprecedented growth in the securitization market, which has evolved into a highly liquid, multitrillion-dollar market that draws investors from around the world. As they have evolved, PSAs have become a critical element of this market.